See below for the specific sections of this pathway. For further information on each section please refer to the attached document.

Pathway 9 - Advocacy

This pathway contributes to change by:

Advocating for appropriate laws and policies that are gender-sensitive and responsive to the needs of vulnerable women, and their effective implementation.

Sections:

This pathway will aim to have an impact on all vulnerable women. All vulnerable women without exception need the protection of a gender-sensitive legal environment, that takes their challenges into account and is implemented effectively.

Read more about the impact group of CARE Rwanda’s VW program in section B1 of the full program document.

CARE Rwanda is committed to work in partnership. In this pathway, our strategic partners are:

- The Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion, who is the main responsible ministry for the implementation of policies that promote gender equality and women empowerment.

- The Rwandan Women Parliamentarian Forum, uniting all women parliamentarians and being a strong advocate for ensuring gender issues are discussed in parliament.

- Line ministries most relevant to the specific advocacy topic (such as the Ministry of Health or the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning).

- Pro-femme, being a forum of all women’s organizations in Rwanda

- UNFPA, who are considered a strong advocacy partner on all issues related to gender, GBV and SRH.

- The National Women’s Council, uniting women’s voices and as such also being a strong advocacy partner.

- The Ministry of Local Government, and especially its social affairs department, who are a crucial partner to ensure that the results of our advocacy efforts reach the local level and are actually being implemented.

- The National Commission of Human Rights, being a constitutional, independent and permanent national organ in charge of the promotion, protection and monitoring of the respect for human rights.

Depending on the issue to be advocated for, CARE Rwanda will work together with partners that are experts in that particular field, such as COPORWA, the network of GBV civil society organizations, or the Rwanda Cooperative Agency.

Apart from the strategic partners, many implementing partners contribute to this pathway. Please refer to our website for the descriptions of the projects under this pathway and get to know our implementing partners.

CARE Rwanda’s work on this pathway will be informed by the Government of Rwanda’s policy context. When it comes to advocacy, any law, policy or strategy mentioned in any of the other pathways is relevant, because in theory, CARE Rwanda’s programming could at some point bring up evidence showing challenging around the formulation or implementation of any of these laws, policies or strategies. If this happens, that particular document will become the subject of advocacy efforts.

For the time being, this pathway includes those documents that are currently most relevant to the advocacy efforts of CARE Rwanda and its partners:

- The Constitution (2003) is highly gender-sensitive and is the basis for gender-equality in other laws and policies. The EDPRS II (2013) includes ‘family and gender’ as one of its cross-cutting themes.

- The Government of Rwanda has ratified several international commitments, such as CEDAW and UNSCR 1325. For the latter, a national action plan towards its implementation is in place.

- The National Decentralization Policy (MINALOC, 2001) is the basis for making the lower scale levels a solid level of service delivery, and as such potentially contributes to an important extent to the effective implementation of many other laws and policies.

- The following laws and policies are all subject of currently ongoing advocacy efforts:

- The National Social Security Policy (MINECOFIN, 2009), including the regulations on U-SACCOs;

- The National Law on Prevention and Punishment of Gender Based Violence (MINIJUST, 2009)

- The National Policy Against Gender-Based Violence (MIGEPROF, 2011)

- The National Gender policy (MIGEPROF, 2011)

- The Law on matrimonial regimes, liberalities and successions (1999);

- The Organic Law Determining the Use and Management of Land in Rwanda (2005);

- The Reproductive Health Policy (MINISANTE, 2003), which is targeted specifically with the objective to improve its implementation for Historically Marginalized people.

Besides the above mentioned policies, a number of laws, policies and strategies are relevant to the VW program as a whole. These are described in section A3 of the full program document

An evidence-based approach to advocacy

CARE Rwanda’s advocacy agenda is based on the analysis of rights deficits. Our approach to advocacy relies heavily on the collection of evidence at the grassroots level, either coming from our ongoing programming or research specifically initiated with the objective to collect evidence.

This evidence can be collected by CARE Rwanda itself, or by other reliable actors, such as our partners. We believe that this evidence should be the basis of all our advocacy activities, whether they are aiming at the development, the review or the implementation of laws and policies.

CARE Rwanda believes in working together to advocate for change. Therefore, we will form or engage in appropriate coalitions, networks, etc. to join forces with likeminded actors. Together with these partners, we will engage in analysis of the evidence collected as well as gender-sensitive analysis of laws and policies related to the issue at stake.

This process will show where the main challenges in existing laws and policies lie, and how these challenges affected the lives of women. As such, it will guide CARE Rwanda and its partners in the decision on what laws, policies and institutions to target with advocacy, or whether advocacy should even aim at creation of new laws or policies.

Based on this, evidence-based messages will be shared with the relevant government actors as well as the wider public. Partners can include both local and international actors. With the aim of capacity building and sustainability, CARE Rwanda aims to give its local partners a leading role in these coalitions and networks. For the same reason, capacity building of our partners on advocacy is an important objective in itself.

As indicated in the strategic partner section above, CARE Rwanda sees those ministries that are responsible for laws and policies that directly affect VW as strategic partners. We aim to build strong relationships with them, in order to engage in constructive dialogue. This dialogue can for example take place at conferences or meetings organized by CARE and the networks it participates in, or by our involvement in ministries’ technical working groups.

An area that CARE Rwanda wants to explore more, is the use of media (and especially radio) as a medium for advocacy. CARE Rwanda sees media as an essential part of civil society and wants to contribute to the development of an independent and critical media. This means that we aim not to work with media as contractors (paying them to broadcast our messages) but as partners, inviting them to do their own analyses on gender issues and challenge them to see it as their role to bring these to the attention of their public.

CARE’s role in this will be to build capacity, to provide information (e.g. by sharing our collected evidence or by organizing field visits for journalists) and to invite media actors as partners to our coalitions. When connecting media with impact groups, for example by identifying strong testimonies that can be used for media, CARE Rwanda will take on the role and responsibility to sensitize and prepare individuals who participate.

Although CARE Rwanda’s advocacy agenda is always flexible and depending on evidence collected in ongoing programming, certain issues have been identified as possible topics for advocacy in the near future, based on evidence so far collected. These include:

- The implementation of article 10 of the national GBV law (preventing violence and catering to the victims of GBV), including:

- The establishment of a ministerial order, which is necessary for the support of GBV victims as it is stipulated in article 10;

- A permanent program of support and assistance for victims of violence, alleviating the suffering and the consequences resulting from the violence suffered by victims of GBV. The government should put in place financial and material resources for their care and social reintegration.

- A sound, gender-sensitive policy to accompany the GBV law and ensure its meaningful implementation;

- The effective implementation and enforcement of laws and policies that allow women to own, inherit and access land, including the Law on Matrimonial Regimes, Liberalities and Successions (1999) and the Organic Law Determining the Use and Management of Land in Rwanda (2005);

- Availability of sufficient resources for adequate health services, especially on SRH, FP and services for women affected by GBV. In this, special attention is given to Historically Marginalized People. As a result of their marginalized position, their access to health services is specifically limited. There is a need for recognition of this problem and action to counter the disadvantaged position of HMP.

- Level of engagement and effectiveness of CSOs in doing effective advocacy on women’s issues

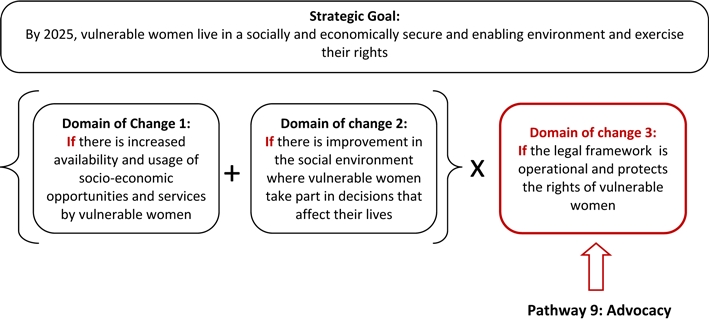

In addition, this pathway will contribute to change at the level of Domain of Change 3, which will be measured through additional indicators at the level of the DoC. Please refer to section D4 of the full program document for these indicators.

- The formation of the GBV Civil Society Network has ensured the presence of a strong partner for advocacy on GBV. The members of the network have been trained on advocacy, and CARE Rwanda partnered with them to provide inputs on several of the GoR’s commitments related to the implementation of their laws and policies related to GBV and gender.

- The national conference on financial inclusion, that CARE Rwanda and its partners held in March 2012 brought together high government officials as well as VSL participants. The conference led to adoption of the VSL model by the government, their enthusiasm and support. Consequently, MINECOFIN and MIGEPROF have highly recommended CARE to implement VSL at national level., and have influenced MFIs and banks to be more flexible in their terms and conditions when giving loans to VSL groups.

- As a result of joint advocacy efforts, civil society is now invited to participate in the multi-sectoral GBV technical working group, organized by MIGEPROF and MINISANTE, while before, the working was made of ministry and UN staff exclusively. Civil society’s presence gives them an important entry point for further advocacy efforts with the ministries involved.

- Policy Advocacy and Learning Initiative (PALI)

- Policy Engagement for Marginalized Inclusion (PEMI) Project

- Great Lakes Advocacy Initiative (GLAI)

- Umugore Arumvwa (Kinyarwanda for ‘A woman should be listened to’)

- ISARO (Kinyarwanda for ‘pearl’)

- Public Policy Information Monitoring (PPIMA) Project

CARE Rwanda is committed to learning, to continuously improve the relevance and quality of its work. In relation to this pathway, it poses itself the following questions:

- How can we work more with the media in our advocacy efforts? How can best contribute to their development as independent actors who are able to report in a non-confrontational manner on sensitive topics?

- How do we engage with impact groups/communities on whose behalf we advocate their rights? How are we accountable to these rights-holders? How can we build their capacities and if needed, protect them from any personal disadvantages?

- What exactly do we want our role to be related to advocacy? Do we advocate on technical issues only, or also for a larger civil society space (especially at the local level)? How do we combine the capacity building of our partners in advocacy with taking our own responsibility in being a visible advocacy actor? How do we balance having the influence that we want with the risk that come with the visibility? And how do we balance our neutrality as a humanitarian actor with being engaged in (possibly sensitive) political discussions? Are we ready to engage publicly in an open and frank dialogue with government actors, policy makers on sensitive issues?

- How can we engage with the national police and the ministry of justice when laws and policies are not respected? How can we collect evidence that not only informs us about the level of implementation of policies, but also of laws?

- How can we use, aggregate, present our evidence collected more efficiently at the national level? How can we become an information resource (based on our experience and evidence) to government for implementation and policy formulation?